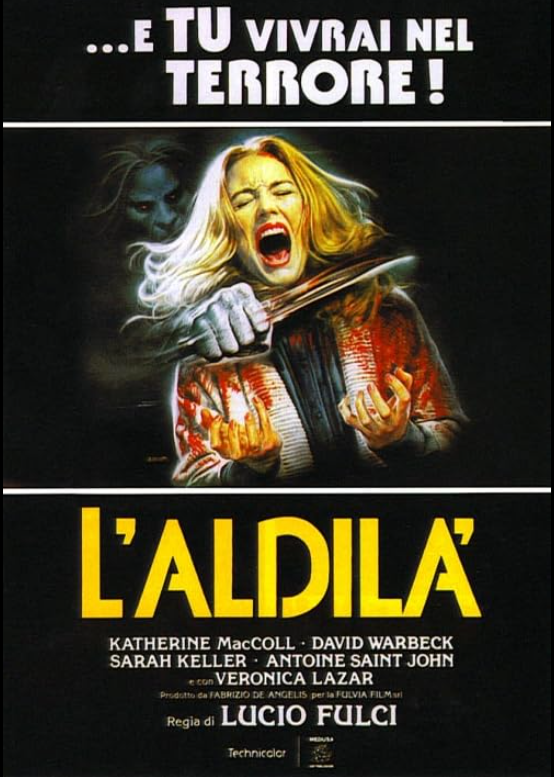

Coming off the commercial success in his Italian home market of Zombi 2 (1979), which was marketed as a sequel of Zombi (Dario Argento´s reworked version of George A. Romero´s Dawn of the Dead), Lucio Fulci looked for a way to extend his winning streak by working some of H.P. Lovecraft’s lore into his particular brand of supernatural grand-guignol cinema. So he rehired writer Dardano Sarchetti (The Ogre, Dèmoni/Demons) and re-booked film score-composer and frequent Goblin-collaborator Fabio Frizzi (Castle Freak, Manhattan Baby) and went on to develop and film what would eventually become his ‘Gates Of Hell’ trilogy. City Of The Living Dead (1980) would be the fascinating and atmospheric but unfocused first effort; The Beyond (L’Aldilà, lit.: the afterlife), the second film in that series, is the most (in)famous, arguably his best, and certainly the wildest and most fascinating of the bunch.

Trying to make sense of The Beyond is a daunting task. The movie was labeled as ‘video nasty’ by the various Anglo-Saxon censor bureaus back in the day, and it didn’t even get a full release in the U.S. before September 1998 – posthumously for Fulci, something that would only add to the movie’s notoriety. Now, well over 40 years after its initial release in 1981, how does it hold up, viewed through today’s eyes? What makes it work the way it does? And what exactly is it all about anyway, what’s the story it’s trying to convey? The latter is already quite a conundrum by itself so let’s get the synopsis, such as it is, out of the way first.

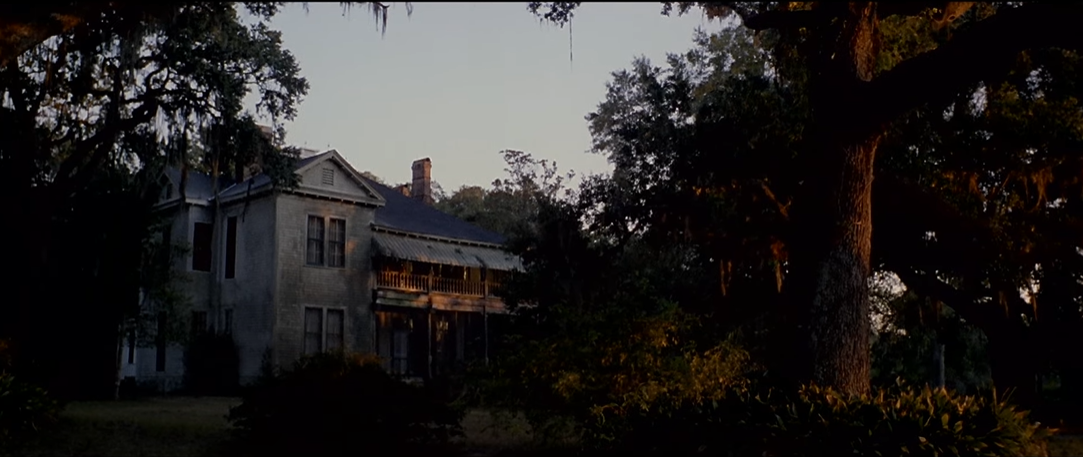

In a sepia-toned flashback intro, a man works on a painting in room 36 of the Seven Doors Hotel in New Orleans, Louisiana. A lynch mob arrives and brutally slaughters him for practicing black magic. As this happens, a white-eyed woman reads from an ancient tome, a grimoire titled Eibon, prophesizing the opening of one of the seven gates of hell. Flash forward to present day (and to full-color) and a woman named Liza Merrill (Catriona MacColl, City Of The Living Dead, The House By The Cemetery) inherits the hotel and moves from New York City to renovate and reopen it.

After a freak accident of one of the construction workers, Liza gets acquainted to local doctor John McCabe (David Warbeck, The Last Hunter, The Black Cat). A plumber arrives to investigate the lack of running water and fix it, and in the flooded basement he uncovers a bricked off area, inadvertently opening a gateway to hell. And by doing so he sets in motion a string of macabre and grueling incidents, culminating in vermin plagues, hordes of the dead rising, and a blind harbinger with a dog (Cinzia Monreale, Beyond The Darkness/Buio Omega, The Stendhal Syndrome) who may or may not be corporeal. Will John and Liza be able to fend off the undead and close the gate to hell before it’s too late?

On the surface, it’s not so difficult to tear The Beyond a new one for its faults. The script is all over the place, with a hotel – where most of the movie is set – that inexplicably gets a different floor lay-out and characters that look spooky for no reason. Some scenes also seem to come out of left field, contributing nothing to the story and feeling spliced in because it seemed like a cool thing to do. It has been argued that this was done as to be intentionally disorienting, and while I can get behind the fever dream logic that the movie follows, I don’t think Fulci’s intentions ran quite so deep. He just doesn’t seem to care about narrative consistency.

Acting performances are also wildly inconsistent and tolerable at best. The actors aren’t helped by what the script gives them, leading to stilted dialogue delivery and lines to the point of ridicule (my favorite: ‘there isn’t a soul here!’). Fortunately, Fulci keeps the relation between John and Liza amicable but low-key and stays away from developing any love interest between them. David Warbeck, well aware of the type of movie he was in, lets his character try to load a revolver through its barrel in a scene, out of sheer goofiness amidst the mayhem Fulci conjures up around him – something that somehow made the final cut.

All this results in a movie that never gains any real dramatic traction or impact. Liza is a bland and passive protagonist, at times getting dangerously close to being a whiny victim of circumstance who never really drives the plot. John serves as a voice of reason amidst all the madness, but is equally bland and neither of them, while sympathetic enough, ever inspire any real emotional investment. The movie is, in short, a mess. But this is also where it gets interesting, because that’s nowhere near the final conclusion. Fulci somehow found a way to make it all work and fall into place.

Looking at The Beyond as a collection of alternately atmospheric and intensely graphic vignettes, tenuously stringed together by a surrealistic story, reveals the mad genius behind it all. The weird dream logic and audiovisual intensity of what Fulci puts on display makes you forego, or at least accept, all the fallacies in the very basics of dramatic groundwork and consistent story telling. Fulci, who’s at the top of his game here, composes a gothic experience in the same vein as Dario Argento did with Suspiria, Inferno and, later, with Phenomena/Creepers. The movie runs at a brisk 90-minutes pace with visuals drenched in atmosphere and gore, accompanied by a unique jazz-rock score rivaling John Carpenter’s level of work in terms of musical identity and recognizability.

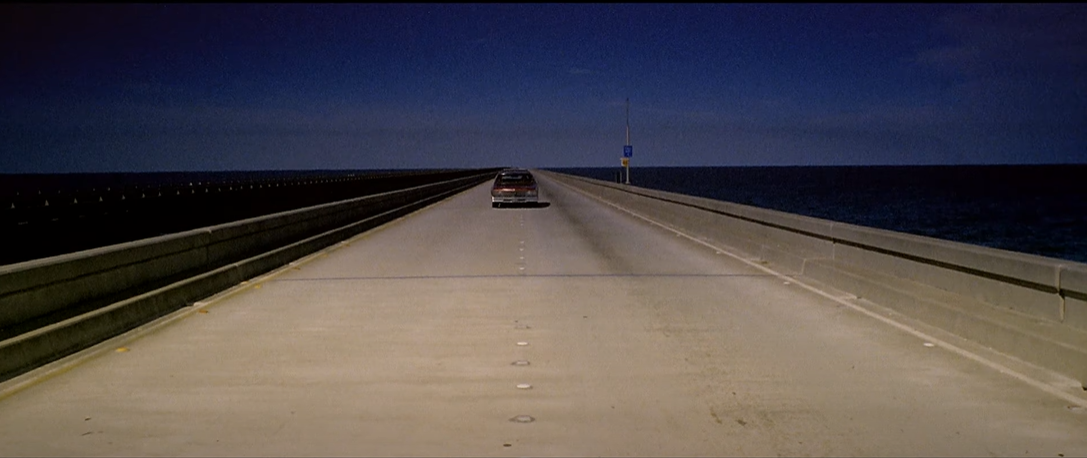

Fulci reduces character development, acting performances and narrative substance to accessories, only there to serve the impact of the motion picture. Of particular note is the unforgettable closing scene, which I would argue still stands as the best depiction of purgatory ever made to this day. Filmed on location in Louisiana and in a studio in Rome, there were, of course, no digital effects available at the time. Everything was done practical with props and make-up, and leave it to Italians (Giannetto de Rossi, Haute Tension, Rambo III, Zombi 2) to make something look graphic and gruesome – the silliness of the bobbing plastic tarantulas notwithstanding. The rich visuals are furthermore deliberately lensed by Sergio Salvati (City Of The Living Dead, Puppet Master).

As I prepared for this review, I rewatched The Beyond with my gen-Z son – an avid movie watcher in his own right – to learn what impression the movie leaves to his contemporary eyes, unhampered by nostalgia. His initial reaction was what I can best describe as bewilderment, which adequately encapsulates what The Beyond is all about. It’s a mess. It’s also a unique viewing experience and arguably the greatest Italian genre movie ever made.